Choosing between “another cup of coffee” and “death” sounds absurd, unless you’re inside a magical story full of curses and oddities, or you’ve read Camus, who argues in The Myth of Sisyphus that the most fundamental question of philosophy is whether to commit suicide or to go on living—whether to face the absurdity of existence or distract ourselves with another cup of coffee. But after watching Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), that choice no longer feels distant from real life. Perhaps it doesn’t belong only to fairy tales or philosophical debates. Maybe it’s something more ordinary, something we all face, though we hide it as if it were too absurd to name.

Think about it: if someone asks, “Are you truly happy with your life?” what would our honest answer be? Is it one that forces us to face reality, or just the story we tell ourselves? This question isn’t really about happiness; It’s about whether we’re willing to confront what truly makes our lives meaningful.

At the end of the play, after a storm of chaos and the realisation that her child, the only thing giving the main character’s life meaning, is actually imaginary. Instead of facing reality, Martha simply chooses to go to bed, akin to taking another cup of tea. Choosing reality is frightening.

This retreat into imagination when reality becomes unbearable is not unique to Martha. We all create stories to protect ourselves from the terrifying emptiness that might exist without them. Maybe that’s why we fear those who don’t choose illusion over reality, people like Virginia Woolf. We, the “normal” ones who prefer to live inside our safe illusions until forced to confront reality, are afraid of those who show us there are other options. People like Virginia Woolf, the great British novelist, who found life unbearable and ultimately took her own life.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is a three-act play that unfolds over a single night in the home of a middle-aged couple, George and Martha. George is a history professor at a fictional New England college, where Martha’s father is the university president. After returning from a faculty party at two in the morning, when everyone is exhausted, drunk, and vulnerable, Martha tells George she has invited a young couple over for drinks: Nick, a new biology professor, and his wife, Honey.

What begins as casual late-night socialising spirals into a series of increasingly hostile “games” the couples play, including Humiliate the Host, Get the Guests, and Bringing Up Baby. The alcohol-fueled evening strips away their pretences as painful truths about their marriages and themselves are revealed.

At the centre of the play is George and Martha’s imaginary son, whom they have invented and nurtured in their minds for years. This illusion becomes the final battleground in their war of words. By dawn, when Nick and Honey leave, George and Martha are left to face a new reality—one without the comforting fiction that has sustained their relationship.

Against this dramatic framework, Albee’s masterpiece unfolds on multiple levels. It has often been interpreted as a portrayal of American society after World War II, exposing the cracks in the American Dream and revealing that families were not as idyllic as national mythology suggested. The play shows how dreams remain unspoken and die when confronted with reality, symbolised by the imaginary child, who disappears once the truth is spoken. It is a shared illusion that survives only as long as everyone agrees not to question it. The moment Martha breaks that rule and tells Honey about the child, their fragile protection is gone.

The main characters’ names—George and Martha—echo America’s founders, while the New England college setting represents the intellectual foundation of American society.

The play also explores deep psychological layers in the marriage between Martha and George, and in the relationship between Martha and her father, a complex mix of love, hate, admiration, and fear toward a cold patriarch. We encounter an orphan shockingly accused of killing his parents, prompting the haunting question: “Did I?” Dysfunctional relationships permeate every interaction. The supposedly affectionate young guests are bound not by love but by money and power. Ultimately, we witness humans so desperate for love and meaning that they create imaginary figures—the child—that vanish when brought out of the mind and into reality.

I want to explore another layer—perhaps a personal interpretation, but one worth examining. At its heart, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is about existential loneliness. Humanity is represented by Martha (whose father is the university president, symbolically representing God), who, with all her playfulness, sins, beliefs, and struggles, tries to find purpose or meaning—except for what she fabricates herself.

Religion (or Tradition) is represented by George, which has accompanied humanity for centuries, protecting us from such loneliness by providing meaning in life. When religion begins to fail, we grasp at new solutions—science and technology, represented by Nick—hoping these might shield us from emptiness and reality.

As the competition between religion and science intensifies, George (tradition) warns that a world built only by science will be soulless and cold. Martha (humanity) also acknowledges this once. In the end, George holds the power to destroy the most important purpose in Martha’s life, her child. After that, humanity is left alone in a cold, empty world.

At the end of the play, Martha doesn’t want to kill her son, but she must. And when everything finally becomes a little calmer, she asks George to go to bed.

Let me explain why I interpret the script this way.

At first glance, some parts of the play don’t seem to make sense. That was my first clue that there might be another layer of meaning. For instance, the play never actually mentions Virginia Woolf (except once in a song). And then, in the middle of a tense exchange between husband and wife, George says:

…so I don’t really hear you, which is the only way to manage it. But you’ve taken a new tack, Martha, over the past couple of centuries—or however long it’s been I’ve lived in this house with you…

Why does he say “centuries”? And why, at the end, does George perform a kind of exorcism in Latin? Why is the child imaginary? These strange details made me think there was something deeper going on.

When George says he has lived with Martha for “centuries,” he’s not only talking about their marriage, but he’s also referring to how long tradition and religion have accompanied humanity. When he performs an exorcism, he’s not just a jealous husband; he’s acting as a priest removing an illusion. And when the child is imaginary, it’s not simply about a couple’s private fantasy—it’s about all the imaginary purposes we create to survive.

Shall we start?

1. Disappointing Games

The play begins with tension between a wife (Martha) and her husband (George). From the start, we see that Martha does not respect her husband. In the first few pages, she describes George as a failure:

“You didn’t do anything; you never do anything; you never mix. You just sit around and talk.”

“I swear … if you existed, I’d divorce you.”“I can’t even see you … I haven’t been able to see you for years ….”

We can see that Martha has no hope for George, but still, these are strange things to say to someone you live with.

Later, Martha says:

Well, maybe you’re right, baby. You can’t come together with nothing, and you’re nothing! SNAP! It went snap tonight at Daddy’s party. (Dripping contempt, but there is fury and loss under it.) I sat there at Daddy’s party, and I watched you … I watched you sitting there, and I watched the younger men around you, the men who were going to go somewhere. And I sat there and I watched you, and you weren’t there! And it snapped! It finally snapped! And I’m going to howl it out, and I’m not going to give a damn what I do, and I’m going to make the damned biggest explosion you ever heard.

This moment shows Martha’s deep disappointment. She believes George has given up, or more accurately, that he has nothing left to offer. George sits there silent, passive, with nothing new to say. He once gave Martha meaning and purpose, but now he simply exists. He hasn’t evolved or adapted to new challenges. Meanwhile, the younger men (like Nick) represent new ideas—science, technology, progress—and they seem full of energy, ambition, and effort, ready to go somewhere. But George has nothing to bring to the table, nothing to give Martha, or humanity.

For centuries, religion answered the big questions: Why are we here? What is our purpose? What happens when we die? But for Martha, George can no longer answer these questions satisfactorily. The disappointment isn’t personal; it’s existential. It’s a nihilistic feeling: that moment when you realise something you once held onto is now empty, and it can no longer give you purpose.

The disappointment isn’t personal; it’s existential.

Martha mentions several times that George is not the head of the history department but only a member of it. She says her father once had great ambitions for George, but after a while, when he saw that George’s potential was low or ignored, he lost interest. Martha emphasises that although George had good opportunities, he failed to use them. Instead of taking on a major role at the university, or even replacing her father as president, he stays just a simple employee, held back by his lack of ambition and effort.

In another part, George says to Nick:

Martha is changing … and Martha is not changing for me. Martha hasn’t changed for me in years. If Martha is changing, it means we’ll be here for … days. You are being accorded an honour, and you must not forget that Martha is the daughter of our beloved boss.

This line also shows Martha’s disappointment with George. She is looking for a new kind of revival, which she finds in Nick, the man of science. George says that “Martha hasn’t changed for me in years,” which reflects the deep disappointment Martha feels toward him.

2. Rivalry Between the Natural and the Supernatural

The tension between George and Nick is visible from the very beginning. Early in the play, Martha says she invited a young couple over after the party, around 2 a.m. She believes Nick, the young man, is one of the new faculty members in the math department.

George is tired and wants to rest, but Martha insists he be a good host to their guests. When George and Nick are alone, George asks, “What were you drinking over at Parnassus?” He wants to know what kind of literature, history, or cultural interests Nick has. This is George’s territory—he represents tradition and religion. He has a long relationship with cultural ideas, and mathematics (which George assumes Nick comes from) is never a threat in this space; in fact, tradition sometimes even uses mathematics for its own purposes. But Nick doesn’t understand what George means, one of the first signs that he is not part of George’s world.

“Parnassus” is a mountain from Greek mythology, the home of art and poetry. George is testing whether Nick knows about culture and tradition. But Nick has no idea. He comes from a different world, the world of empirical facts, laboratories, and biological experiments. They don’t speak the same language.

When George realises that Nick is actually a biologist, his reaction is revealing. Albee’s choice of biology (especially in the 1960s) reflects how much attention the field was getting at the time, as people hoped biology could finally decode the secrets of human life. George responds:

You’re the one! You’re the one who’s going to make all that trouble … making everyone the same, rearranging the chromosomes, or whatever it is. Isn’t that right?

From George’s point of view, Nick is the one causing trouble. He sees science as a threat to his territory and its claim to explain how the world works. In the 1960s, when Albee wrote the play, science was promising incredible things—decoding DNA, curing diseases, even engineering better humans. To George, this is dangerous. There’s a moment when he realises this is not just personal rivalry but it’s a competition between two worldviews.

Soon after, George discovers that Martha has told Honey about their child—something that was forbidden. It seems there was a secret between George and Martha, and Martha has broken it. This moment shows Martha as a symbol of humanity—someone who finds something powerful enough (like Nick, or science) to reveal old secrets.

Another sign for George is when Martha changes her clothes to become more comfortable. This is when George says:

Martha is changing … and Martha is not changing for me.

George tries to show that the world created by science is not worth living in. It’s a world of soullessness and boredom—a world without culture or art, without music or painting. As George says, “Naturally, I am the opposite of all of them.”

Later, Nick reveals to George that he married his wife not purely for love, but because her father was rich. There was an instrumental purpose. He also says that Honey started to “blow up,” so they thought they were going to become parents and got married, but then she “blew down,” and he doesn’t know why it happened.

This suggests that science doesn’t necessarily do better than religion for humanity. There is no pure sincerity. Science promised to give us control over life itself, to create and manage our lives meaningfully. But Nick, as the representative of science, cannot even create a real child. He can only create false hope—“blow up and blow down.” Science is not better than the previous dominant power, religion; it simply pursues its own goals and sees humans as tools. If religion could provide a “child” (a symbol of meaning or purpose), science cannot even provide that. It offers only utopia and disappointment (blow up and blow down). I will explore this further later.

One of the most powerful moments showing the deeper debate behind the surface of marriage is when George tells Nick how his efforts have failed:

You take the trouble to construct a civilization … to … to build a society, based on the principles of … of principle … you endeavor to make communicable sense out of natural order, morality out of the unnatural disorder of man’s mind … you make government and art, and realize that they are, must be, both the same … you bring things to the saddest of all points … to the point where there is something to lose … then all at once, through all the music, through all the sensible sounds of men building, attempting, comes the Dies Irae. And what is it? What does the trumpet sound? Up yours. I suppose there’s justice to it, after all the years … Up yours.

It seems George is saying that despite all his efforts to make human society civilised, he has failed. When George realises Nick is a powerful competitor, he senses that his own era may soon be over. That’s why he mentions the Dies Irae, the Latin hymn of the Day of Judgment. George means that no matter how much civilisation and meaning you build, death and destruction always come. All the culture, all the art, all the moral systems—they all end with “Up yours.”

George sees his replacement (Nick) arriving, and he knows Nick will fail, too. It’s a warning from the old king to the new: you may try to build something valuable, but sooner or later, it will collapse.

3. The Exorcism of Reality

Martha expresses a mix of emotions and contradictions toward Nick—behaviours that he cannot understand. Eventually, he says to her, “You’re crazy too.” Before this, Martha and Nick flirted, but once she reached out to him, she began to treat him the same way she treats George. When someone knocks at the door, Martha orders Nick to answer it as if he were her servant.

Earlier, when Nick tells Martha she’s crazy too, she calls him a “flop.” This moment is crucial. Martha had placed her hopes in Nick—she thought maybe science could give her what religion and tradition could not. But after being with him, she realises he’s empty as well. He becomes just another disappointment. She even admits that he once seemed to have more potential than anyone she had met in a long time, but his performance shows that he’s also a failure, just like all the others.

After Nick claims that all men, including George, are flops, Martha replies:

You’re all flops. I am the Earth Mother, and you’re all flops. (More or less to herself.) I disgust me. I pass my life in crummy, totally pointless infidelities … (Laughs ruefully.) would-be infidelities. Hump the Hostess? That’s a laugh. A bunch of boozed-up … impotent lunk-heads…

This dialogue shows that the play is much more than a story about a marriage. When Martha calls herself the ‘Earth Mother,’ she is saying she has offered herself to many men who seemed promising. She offered them courage, strength, and intimacy, but they all failed her. These “infidelities” are not sexual. They represent humanity’s repeated search for meaning through new systems of belief—each one promising to make us happy, and each one ending in disappointment. Every new ideology or faith becomes another “flop.” Martha has come to realise that all these pursuits are meaningless and that she may never be happy again.

Then she says:

There is only one man in my life who has ever … made me happy. Do you know that? One!

She means George.

The first time humanity was promised a better world, something larger than itself that could give life meaning, it came from religion. Within those systems and powers, the world felt coherent and meaningful. People believed that everything had its rightful place, grounded in something greater. Humanity was happy then, and has perhaps never been happier than when it believed in that certainty.

Alternatives like science couldn’t give us the same feeling that we are not alone. When we believed, there was certainty; within a system like religion, we felt clear and complete. But once a flaw appears in that system, once certainty disappears, nothing can restore that same feeling, the sense of not being alone, the quiet assurance that there are still things we truly know. Martha’s love for George is a love for the past, for the time when she had absolute faith in him. After that, she could never feel the same again.

When Martha tells Nick, “You don’t believe it,” and Nick insists, “No, I do,” she replies, “You always deal in appearances.” Why does she say this to someone she has only just met, and with such certainty? This isn’t just about Nick as a person; it’s about what he represents: science. For Martha, science cannot reach the human inner world. It remains cold, rational, and superficial, concerned only with appearances. It cannot touch the emotions, contradictions, and paradoxes that define human life. Science cannot explain why we need illusions to survive, or why we invent imaginary children to give our lives meaning.

The conversation between Martha and Nick captures this tension perfectly:

MARTHA: Oh, little boy, you got yourself hunched over that microphone of yours…

NICK: Microscope…

MARTHA: …yes… and you don’t see anything, do you? You see everything but the goddamn mind; you see all the little specks and crap, but you don’t see what goes on, do you?

NICK: I know when a man’s had his back broken; I can see that.

MARTHA: Can you!

NICK: You’re damn right.

MARTHA: Oh… you know so little. And you’re going to take over the world, hunh?

NICK: All right, now…

MARTHA: You think a man’s got his back broken ’cause he makes like a clown and walks bent, hunh? Is that really all you know?

Here, Martha humiliates Nick (science) as a “little man,” mocking his claim that science will take over the world. This is not a rivalry of love; it is about which force will rule humanity next, after George (tradition) becomes the fading king.

At the end of the play, George invites them to play the final game to the death. He begins to talk about their son, though Martha resists, perhaps because she has already realised that Nick cannot offer the power or comfort she sought. Earlier, it was Martha who broke the rule by speaking of their son; now it is George who reopens the topic. Previously, George had told Honey that their son was dead, though Martha did not know it yet.

George accuses Martha of behaving toward their son in an inappropriate, almost erotic way, saying that the boy was ashamed of it. George implies that humans project their sins and desires onto everything they create. Even our illusions—our gods, ideals, meanings—become corrupted by our own weaknesses.

As Martha speaks tenderly of their son, George begins chanting Latin prayers in a ritualistic tone. This, in my interpretation, shows that George represents an old spiritual power. The chant is a ceremony linked to death and exorcism, a symbolic act of mourning and, more importantly, an exorcism of the imaginary son.

Martha describes the child as someone who protected them (wife and husband) from George’s weakness. But the child (the illusion) actually protected Martha from reality itself. It gave her strength and purpose, shielding her from emptiness. When she broke the rule and revealed their secret, George destroyed the illusion as a final act to demonstrate how fragile she is without it.

In fact, this imagined child gave Martha the strength to carry on. It wasn’t something that protected her from George, but it was something that shielded humans from reality, from confronting all their weaknesses and unanswered questions that George (tradition) could not resolve. When she breaks the rule and reveals the secret, George—as the final arrow—exorcises the illusion, showing how fragile she is without it.

George tells Martha that their son has died. The scene unfolds with heartbreaking intensity:

MARTHA: NO! NO! YOU CANNOT DO THAT!

MARTHA: You cannot. You may not decide these things.

NICK: (Tenderly.) He hasn’t decided anything, lady. It’s not his doing. He doesn’t have the power.

GEORGE: That’s right, Martha; I’m not a god. I don’t have power over life and death, do I?

MARTHA: YOU CAN’T KILL HIM! YOU CAN’T HAVE HIM DIE!

GEORGE: I can kill him, Martha, if I want to.

MARTHA: HE IS OUR CHILD!

GEORGE: AND I HAVE KILLED HIM!

MARTHA: NO!

GEORGE: YES! (Long silence.)

GEORGE: (Tenderly.) I have the right, Martha. We never spoke of it; that’s all. I could kill him any time I wanted to.

MARTHA: But why? Why?

GEORGE: You broke our rule, baby. You mentioned him… You mentioned him to someone else.

MARTHA: (Tearfully.) I did not. I never did.

GEORGE: Yes, you did.

MARTHA: Who? WHO?!

HONEY: (Crying.) To me. You mentioned him to me.

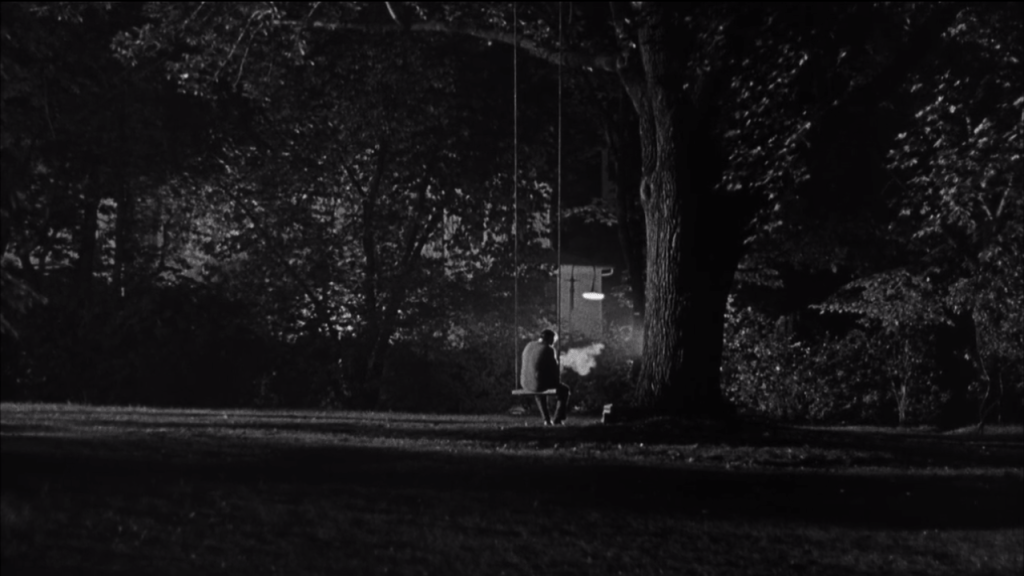

After this emotional climax, the guests (Nick and Honey) leave. The chaos subsides. George gently asks Martha if it’s time for bed. She’s exhausted and says yes.

Finally, George places his hand on Martha and softly sings:

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?…

Martha answers:

I… am… George… I… am…

This final scene is one of the most luminous moments in modern drama. It captures the loneliness of being human, and the ways we escape it. It’s not merely about confronting reality but about the choice we make. George can offer Martha an illusion—a child, a meaning, a purpose—but if she breaks the rule and seeks another source of meaning (like Nick), he can take it away. Without the illusion, she must face the harsh reality, the unbearable emptiness of a world without meaning, without something to hold onto like her child.

Virginia Woolf chose to face that reality, and it destroyed her. But most people cannot. We live through our illusions, and that is not a wrong choice, but it is part of being human. We may search for alternatives to what we once had, but the process is painful and constantly reminds us of our solitude.

Science may serve as a modern alternative, but it remains cold and logical. It cannot provide what religion once did—a living sense of purpose. Science cannot give a real child; it only gives false hope, like Honey’s “blow up” and “blow down” pregnancy.

We fear Virginia Woolf because she chose truth over illusion, because she forces us to leave our shells and confront the world. But the consequences for her were costly. We don’t know what awaits us behind our choices, but it’s worth thinking about before something controls us simply by threatening to take away our illusions.

We fear Virginia Woolf because she forces us to leave our shells and confront the world.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is not just a play about a dysfunctional marriage; it is a profound reflection on the human condition, an existential exploration showing how we rely on illusions to make life bearable and meaningful. It asks: what lies are we willing to believe to survive? To whom do we give the power to control those lies? And most importantly, which lies do we choose to embrace? We should remember that these lies can destroy us at any moment (like George) or offer false hope (like science). But whatever we believe, Albee forces us to confront the question: what are we truly afraid of? Will we face our fear, or simply have another cup of tea and go to bed?